Faced with the unbelievable loss of species, how do we make sense of the seemingly inevitable?

Faced with the unbelievable loss of species, how do we make sense of the seemingly inevitable?

We need to be prepared for a great absence in our culture. In the weekend's UN report on the decline of species - whose rightful demand on media space was so quickly eclipsed by the news of a royal son, as if to underline our human dominion over the natural world - yawning gaps open up ahead of us. A world without a million species.

- Current global response insufficient;

- ‘Transformative changes’ needed to restore and protect nature;

- Opposition from vested interests can be overcome for public good

- Most comprehensive assessment of its kind;

- 1,000,000 species threatened with extinction

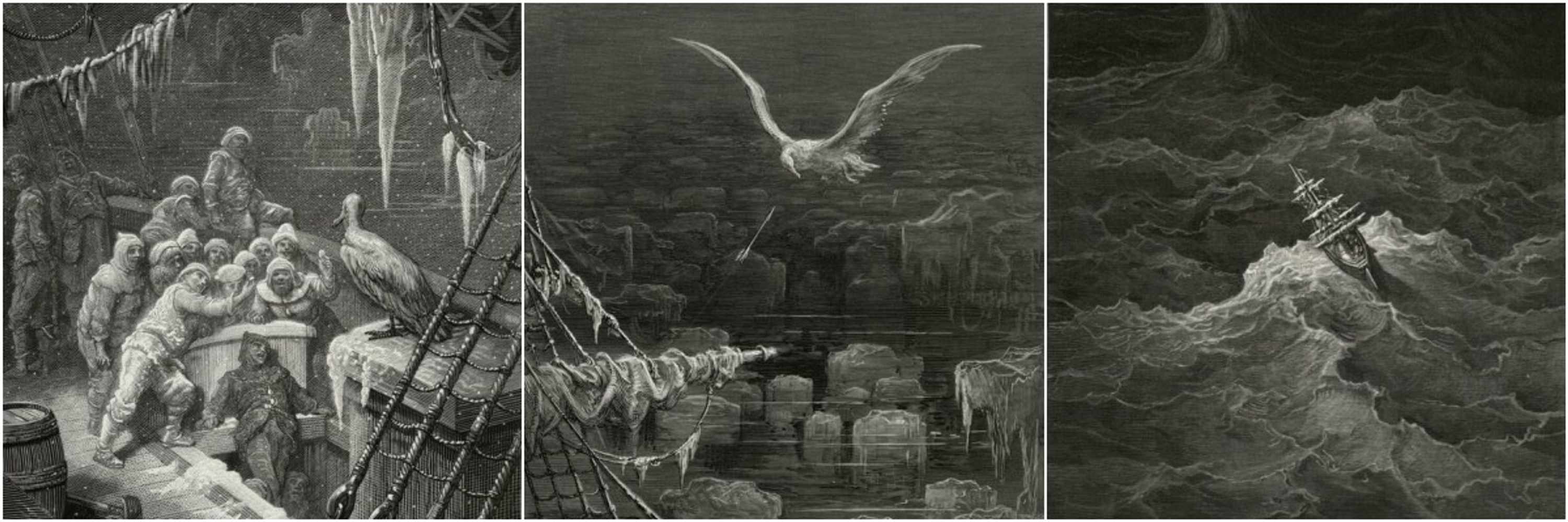

The sheer subtraction of this mass from our planet defeats us. It's just too big to comprehend. Yet paradoxically, perhaps only our culture can ready us for this shock. Two hundred years ago Samuel Taylor Coleridge established the founding fable for our age when he hung the dead albatross around the neck of the Ancient Mariner.

I looked upon the rotting sea, And drew my eyes away; I looked upon the rotting deck, And there the dead men lay.

His poem was an augury of the age of industrial-scale extinction. In the 20th century we killed 3 million great whales. The sheer removal of that vast biomass from the still unpolluted, unplasticised oceans, probably accelerated climate breakdown. (Their faeces alone would have fertilized the food chain, and enabled plankton to sequester carbon from the skies).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M18HxXve3CM

The whale became our albatross around our necks. An emblematic absence, an echo of the fact that its very greatness seemed to allow our vast depredation. That we simply couldn't believe our actions could have a real - deadly - effect on such huge and rarely seen animal.

The whale's fate became a new founding fable of the environmental movement. The Save the Whale campaign of the 1970s is the direct ancestor of Extinction Rebellion. And as the recording of whale song was the enabler of those early attempts to halt that remorseless progress, so fifty years later, we ask ourselves, what have we done? Humpback and minke whales may recover their pre-whaling numbers by 2050 - if all goes well. Blue, fin and right whales certainly will not. We did Save the Whale. Trouble is, it looks like we're about to lose it again.

It is easy to emote about whales, say the sceptics. Like the giant panda, the elephant, the rhino and the orang-utan, they're cuddly, soft-toy friendly symbols of threat. It's why even Andy Warhol, that great ironist of modern culture, created day-glo screenprints of those animals to publicise their plight. (The results looked like a menagerie transported to the dancefloor of Studio 54). The serious people look askance at such populism. The apocalyptic language of the UN report is subsumed by social media. What could a psychedelic rhino do?

But as a senior marine biologist remarked to me the other day - with the long-suffering exhaustion of someone having to deal with the destruction of the organisms he has spent his life trying to explain - sometimes only artists and poets can propose a solution. We endlessly anthropomorphise nature - but culture and history has proved that this fault has a marvelous effect - of stirring us out of our complacency, by proposing our ancient connectivity. Trees talk to each other.

We are all part of the same; the same atoms, the same instincts. If we came from the stars, then we might end up in a black hole. (It's no coincidence perhaps, that we have finally photographed the greatest of all absences).

Extinction Rebellion succeeded in knocking all news stories off the Easter agenda by proposing a new cultural resurrection. That of a positive, cultural protest. They use elements of pop art, of 70s and 80s protest by staging events that are more like art installations: a red-draped Greek chorus bearing witness; a row of glued-together visored sci-fi figures bar the way to the London Stock Exchange. These are clever quotes from human culture. They use humour and art in the way that the shock of the science cannot.

No-one knows how we will deal, culturally, with the culling of the Earth's species. What new fable or narrative can we invent to make sense of what we've done? The UN report proposes unconscionable absences: 35% of marine mammals may be lost in this century. The terrible truth is that we cannot even imagine that new removal - any more than we can imagine the loss of an even greater percentage of the insects and zooplankton that are already, is almost invisibly, destabilising our planet's ecosystem - it is only our imagination that can make any sense of it.

In the 19th century, Coleridge's Ancient Mariner, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and Melville's _Moby-Dick _all warned us, in their creation of modern myths, of what was to come. It's taken us 200 years to take notice. 200 years hence, what fable will our descendents look back on to make sense of the slaughter?

What excuses will they offer for us?

_copy.jpeg?w=100&q=45)