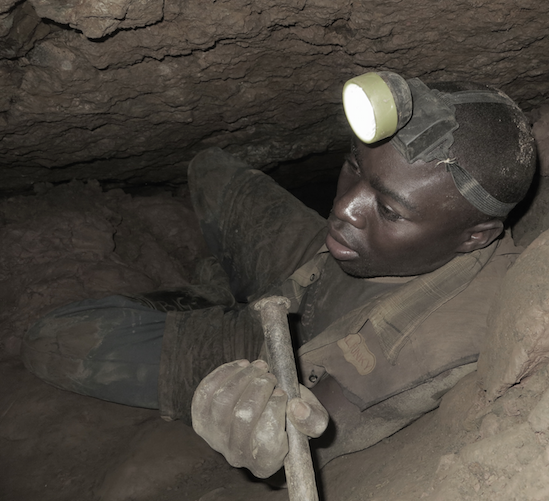

Stigmatizing the Congo’s mineral supply chains is not a panacea for peace, and does not address unsustainable patterns of consumption By Ben Radley  Congolese miners at a tin mine in the eastern DRC

Since the beginning of the first Congo War in 1996, and particularly since the coltan boom of the early noughties, numerous international organisations – including the United Nations – have documented the rise of armed groups in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) that control the production and export of minerals as a means to raise revenue. More recently, powerful advocacy organisations launched a campaign connecting this phenomenon to the electronics used in our daily lives, helping to coin the terms ‘blood mobiles’ and ‘conflict minerals’. The most notable of these organisations, the Enough Project in Washington D.C., recruited a plethora of celebrities to help promote the campaign’s message, including Ryan Gosling and Nicole Richie (see videos below). The campaign was and continues to be a huge success. In 2010, US Congress responded to the pressure and passed a law requiring all companies registered on the US stock exchange to prove that minerals they source from the Congo are not financing armed conflict. Earlier this year Canada passed similar legislation, and the European Union is set to follow suit in 2014. Yet while the campaign narrative plays well into Western stereotypes of greedy African savages raping women while high on dope and opium, it’s only a partial analysis of the situation, mistaking symptoms of conflict for causes. In reality, cleaning up the Congo’s mineral supply chains has about as much to do with building peace for the African nation as David Cameron and hugging hoodies has to do with building a fairer and more equal Britain. Nadda. [caption id="attachment5463" align="aligncenter" width="549"][](https://cdn.ecohustler.com/media/2019/03/19/2013-11-21-08.42.38-pm.png) Working conditions are tough, but artisanal mining provides an essential livelihood to millions in the Congo[/caption] To paraphrase Congo political analyst [Jason Stearns](http://www.obamaslaw.com/the-experts/jason-stearns/), minerals are not what the conflict was about at the beginning, and they’re certainly not what the conflict is about today. Armed groups in the DRC are not fighting over access to and control of minerals as an end in itself, but as a means to finance their operations to address other grievances, namely unresolved political issues pertaining to land, citizenship and territorial boundaries. More importantly still, anything that makes money is a target for armed groups. The eastern DRC is a war economy. Timber, charcoal, palm oil, cannabis, poaching, illegal taxation of populations, road checkpoints. Cleaning up one of these sectors without addressing the conflict’s root causes simply shifts the violence and extortion elsewhere. The M23, perhaps the most well-known armed group in the eastern DRC today, [does not seek to control mining areas or attack mines](http://www.ipisresearch.be/publicationsdetail.php?id=390&lang=en). Lastly, Congolese state officials are today responsible for the largest part of all human rights violations.[[i]](#edn1) These same officials are now being empowered and entrusted to determine whether a mine’s minerals are fit for export to the international market. One rotten apple is simply being replaced with another. Until serious political reform takes place, it is difficult to see how punitive measures focusing on the eastern Congo’s mineral sector – the single largest employer in the region after agriculture - will lead to an improvement in the daily lives of the Congolese. Of further concern is that the conflict minerals approach has nothing to say to the environmental costs of mining or our mass consumption of electronics. In fact, it encourages the establishment of industrial mining in place of the often less environmentally damaging practice of artisanal mining, as the closed supply chains operated by industrial mines are more easily able to conform to the requirements of mineral certification imposed by conflict minerals legislation than the open and complex supply chains of artisanal mining. Livelihoods are lost at the risk of greater environmental damage and increased capital flight. This is the mining future the eastern DRC now faces, and indeed, [the social and economic devastation caused by conflict minerals legislation in the region has been well documented](http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/08/opinion/how-congress-devastated-congo.html?r=0).[[ii]](#_edn2) This is perhaps largely why the conflict minerals agenda has gained so much traction in political circles. It provides politicians with their favourite magic formula of a humanitarian campaign holding the promise of great change which actually - by failing to address critical political, structural and environmental issues – promises nothing more than business as usual. And we all know, that’s no longer an option. So, what are the options then? Here’s a few alternative approaches that might bring more meaningful and constructive results:

- Westerners looking to have an ethical consumer footprint should look to consume less and push hard for corporations to put in place circular supply chains – i.e. taking back old phones and reusing the minerals – and reduce the practice of built-in obsolescence, rather than making simplistic demands for action in a complex war-torn region.

- Westerners wanting to support the Congolese people should read this article on reclaiming activism from the policy lobbyists in Washington D.C., London and elsewhere, and follow its three core principles: activism should be undertaken in partnership with affected people, under their leadership; activism should seek truth and speak truth; activism should challenge power.

Against these basic standards, the celebrity-led campaign for change in the Congo has - in different measures and at different times - come up short. It’s time for a new kind of advocacy. One that speaks truth to power, not half-truths on behalf of power. ---- The team behind this article are making a film. Obamas Law is going off HERE [caption id="attachment_5462" align="aligncenter" width="1024"] Early morning at a small mining village in the eastern DRC[/caption]

SUPPORTED BY HEROES LIKE YOU

Support independent eco journalism that drives real change.[[i]](#ednref1) Autesserre, Séverine (2012). Dangerous Tales: Dominant Narratives on the Congo and their Unintended Consequences_, in: African Affairs Vol.111, No. 443, pp. 202–222.

[[ii]](#ednref2) Seay, Laura (2012). What’s Wrong With Dodd-Frank 1502? Conflict Minerals, Civilian Livelihoods, and the Unintended Consequences of Western Advocacy_. Working Paper, Centre for Global Development, Washington.