By Ashok KumarA version of this article originally appeared in _[Ceasefire Magazine_]

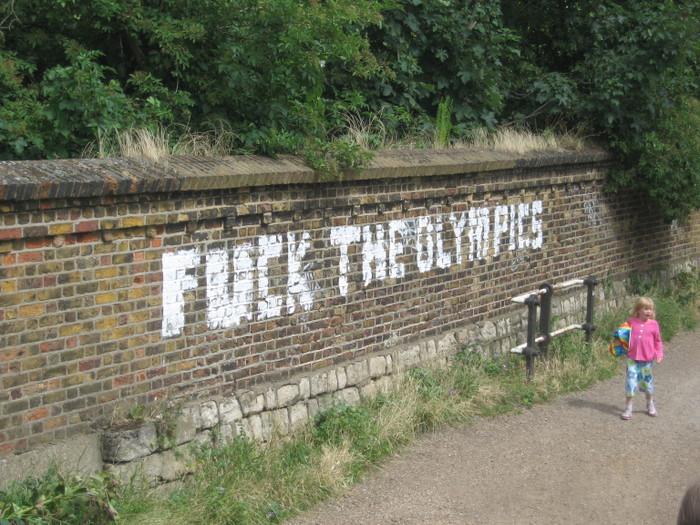

As London prepares itself to host the 2012 Summer Olympics startlingly little critique has surfaced in the mainstream press. With the exception of the trivial issue of ticket prices and, more recently, the overall expense, most London residents remain enthusiastic for the Games. The Olympics, as an institution, has almost always taken billions of pounds, yen, dollars of their host countries’ tax revenue to build magnificent stadiums and housing facilities to intensify institutional racism, militarize the city, trample civil liberties and construct elaborate instillations with a two-week shelf life. London 2012, originally expected to cost £2.4bn is now projected at £24bn with contracts rewarded to some of the most egregious companies and global human rights violators.

Some on the left have remained critical of this massive transfer from public to private at a time of austerity. Though, the London overspend is couched by officials as a one off, a glance at the history of the Olympics show that cost underestimation is part of the Olympic experience; the 1976 Montreal Olympics took over 30 years to pay off the debt it accumulated as a result of its overspend; the 2004 Athens Olympics went one thousand percent over budget to €7.2bn ($12.2), believed by some to have significantly contributing to Greek’s deficit, and the 2010 Vancouver spent six times its original projection of $1bn. In fact, barring the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, where bottom-up pressure forced the city to commit zero public dollars to the Games resulting in a $233 million surplus, the Olympic games always exceed their projected expense, saddling cities with years of debt – often paid back through cuts in services, regressive taxes and increased fares. [](https://cdn.ecohustler.com/media/2019/03/19/Olympic-Gentrification-Area.jpg)Sanitizing the City In recent days some attention has been given to London’s policy of ‘cleaning the streets’ of sex workers. If Olympic history is any indication, the recent actions are only the beginning of a comprehensive strategy to restructure the character, makeup and politics of the city. Targeting sex workers and the homeless first, the decision-makers quickly move towards clearing out minority and working class area from their city. The Olympics have always been utilized as a means to pursue what David Harvey calls ‘accumulation by dispossession’ through ‘creative destruction’ and visible policies of forced evictions to the veiled ones of gentrification. This process is intimately connected to expanding the landscape for capital accumulation, and likely, a prime motivator of Olympic host cities. Thus, the Games are not simply utilized to ‘cleanup’ the city, but to fundamentally reconfigure the city, to ‘cleanse’ it of its poor and undesirable, to not only make way for a city by and for the rich, but to expand the terrain of profitable activity. In order to understand where London is headed it is important to understand how the Games have effected previous cities. The real outcome of the Olympics is often found long after the crowds have gone home. The devastation inflicted on the poorest communities is not simply an adverse side effect, but go to the heart of why cities battle to host the Games. [caption id="attachment2980" align="aligncenter" width="478" caption="A man being forcibly removed from the peaceful protest at Leyton Marshes (April 2012)"][](https://cdn.ecohustler.com/media/2019/03/19/marshes-eviction-leyton.jpg)[/caption] In 2007, the UN-funded Centre for Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE) [released a report](http://www.ruig-gian.org/ressources/Report%20Fair%20Play%20FINAL%20FINAL%20070531.pdf) detailing the effects of the Olympics between 1988 and 2008. Beginning with the 1988 Seoul games, which witnessed the ‘redevelopment’ of 48,000 buildings and the eviction of 720,000 people, where it was used to [accelerate the process of neoliberalism](http://books.google.com/books?id=AsZLRP4VPNwC&pg=PA82&lpg=PA82&dq=neoliberalism+seoul+1988+olympics&source=bl&ots=9aa4LAOPV&sig=X2EDOLcBDWgl-Iq1Ry1S4IpsSI&hl=en&sa=X&ei=nqiFT4e4EaHW0QHe1PXmBw&ved=0CDQQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q&f=false), leading to a ‘drastic rise in housing prices’, transforming Seoul from a city maintained by ordinary people to one that most efficiently entices and reproduces capital. Beyond state-backed mass evictions, the COHRE report shows that the Olympics hasten the process of inflating real-estate prices. In the 2000 Sydney Olympics, for example, between 1993, the year it was selected, and 1998, rents in the city shot up by 40%, whereas in the same period neighboring city Melbourne saw only a 10% rise. [caption id="attachment2981" align="alignright" width="328" caption="Izzy, the Blue Turd, mascot of the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games"][/caption] The 1996 Atlanta Olympics resulted in the demolishing of 2,000 public housing units - evicting 6,000 residents, in addition to the 30,000 residents who were displaced as a direct result of gentrification brought on by the Olympic ‘development’. As if to say the poor and black of Atlanta had not suffered enough, the city issued over 9,000 arrest citations for the cities homeless population as part of a concerted ‘clean up’ effort, a kind of ‘two-week face lift’. In addition, the COHRE report revealed that the Atlanta police were given pre-printed arrest citations with the description “African-American, Male, Homeless” already etched in, while only the date and arresting officer’s name were left blank. At the time the New York Timesreported that the Atlanta urban renewal projects saw ‘virtually every aspect of Atlanta’s civic life transformed’ where in the Summerhill neighborhood adjacent to the Olympic stadium, for example, 200 slum houses had been leveled, where “clean, colorful subdivisions have risen in their place”. As one business owner candidly explained, speaking of the poor and homeless “even if it means busing these poor guys to Augusta for three weeks and feeding them, we ought to do it. It sounds very brutal for me to say it, but they can’t stay here for the Olympics.” A similar trend is found in the 1992 Barcelona Olympics where the study found that in addition to 2,500 evictions, housing prices in the city from 1986, the year it was selected, and 1993 rose by 139% for sale and 145% for rentals, and the same period saw a 76% decrease in public housing availability. In addition, the areas surrounding the Olympic Village site witnessed the displacement of over 90% of its Roma population. City officials made it clear in a public plan two months before the Games began that they intended to “clean the streets of beggars, prostitutes, street sellers and swindlers” and “annoying passers-by”. The report claims that Olympics-induced gentrification led to more than 59,000 residents being driven out of Barcelona. In 2004, a ‘cleaning operation’ was announced by the Greece government against its Roma population in which the COHRE study claims that “authorities merely took advantage of the fact that public attention was focused on the Olympic Games that were underway in order to quietly evict Roma.” The 2008 Beijing Olympics, with its forced displacement of 1.5 million residents, drove out the poor, rural migrant, living at the city’s outskirts, with watchdog groups claiming that relocation saw declines in living conditions by as much as 20%. More recently, the 2010 Vancouver Games, like its predecessors, were held in the poorest section of the city – the Downtown Eastside, and targeted the homeless, indigenous, and sex workers with eviction notices, ordinances banning begging, sleeping outdoors, and a law criminalizing placards, banners or posters that do not ‘celebrate’ the Olympics and ‘create or enhance a festive environment and atmosphere’. Thousands were driven out of their homes, public housing stock shrank and landlords evicted tenants to place properties back on the market for double the rental rates. As Downtown Eastside resident, Kim Kerr, stated “Thousands of people have lost their homes since this city was awarded the Olympic games. There’s simply no place for these people to go. People in the Downtown Eastside die on the streets.” Policies of ‘cleansing’ have already begun in the favelas that encircle the 2016 host city Rio de Janeiro, where 6,000 poor residents have been forcibly evicted at gun-point, alongside a government policy of ‘pacification’ involving over 3,000 military personal invading to ‘take control’ of targeted areas resulting in street battles and the death of more than 30 residents. The Associated Press has shown that in 2010 alone that 170,000 people were facing housing loss due to the double threat of the 2016 Olympics and 2014 World Cup. The Right To the CityHarvey (2008) sees the right to the city as more than the liberty of individuals to access the resources of the city. It is the collective right of people to exercise power in order to shape, transform and remake the process of urbanization. To Harvey “the freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.” The limitation of demands to public handouts can be found in the lead up to the London games. Citizens UK, the countries largest community organization, has astonishingly traded the plunder of areas where many of its members reside for a few crumbs to entrench its trademark ‘living wage Olympics’. Few in the mainstream have taken issue with the crises of housing prices and evictions. In addition, Harvey (2008) argues that the development of capitalism is intimately connected to the emergence of cities, which require a concentration and endless search of profitable terrains for capital-surplus product with a cycle of compounded extraction, reinvestment, and expansion, hence, “the history of capital accumulation paralleled the growth path of urbanization under capitalism.” This partly explains why the areas that border the London Olympic Park are some of the most working class in the country. In fact, almost every Olympic host chooses to situate its site in the poorest neighborhoods of its city. The areas targeted, like London’s East End, LA’s South Central or Chicago’s South Side, are not only the poorest but also maintain the highest concentrations of non-white and minority communities in each city and London’s East End has the highest black and minority ethnic (BME) population in the country. In London the process of forced evictions began immediately after the bid was announced with the demolishing of Clays Lane Housing Co-op and the eviction of 450 residents. _Red Pepper Magazine_ quotes one of the residents at the time, Julian Cheyne, who said, ‘compulsory purchase is a brutal process and from day one the Clays Lane community was lied to while promises were made and broken without a second thought’. Short-term evictions and long-term gentrification go hand-in-hand. In some parts of the city, closer to the Olympic site, poor residents are being forced from their homes while beautification ‘development’ and ‘regeneration’ projects in areas as far out as Dalston Junction or Hackney’s Broadway Market have demolishing a squatted social centre and theatre, whilst Council appointed agents selloff public land to be converted into luxury flats by developer cartels. As with previous host cities, the displacement of residents is not limited to direct government policy. In some East London boroughs landlords have begun evicting tenants where rents are fetching fifteen times their standard rates where flats are now being advertised as “Olympic lets” and landlords are imposing hefty “penalty” clauses for tenants who refuse to leave. Campaigners recently camped out in the Leyton Marshes to refuse attempts by the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) to convert the public space into an Olympic training facility. Indeed, in the past some campaigns have succeeded in their resistance to the Games and its affects. A notable example is the broad-based coalition of housing and labor activists of No Games Chicago, largely credited for foiling its city’s attempt to host the 2016 Olympics, even after pleas from Barak and Michelle Obama. Anti-Olympics organizers in Chicago had been so successful, despite a multi-million dollar barrage of pro-Olympic propaganda to ‘cleanse’ the working-class South Side, that days before the Olympic Committee vote the Chicago Tribunefound that a majority of the city opposed the bid than supported it and 84% opposed using public money to support the games. In Rio de Janeiro, the thousands of slum dwellers who have been given eviction notices are refusing to go quietly; instead the poor have long prepared to fight and are now putting up a historic resistance in the courts and the streets. With unions holding strikes in at least eight host cities of the 2014 World Cup, and a nation-wide movement of 25,000 World Cup workers have threatened prolonged strike action. In a New York Timesreport, a resident, Cenira dos Santos, said of the Games, “the authorities think progress is demolishing our community just so they can host the Olympics for a few weeks, but we’ve shocked them by resisting.” With a few exceptions, the story of each host city remains the same. Once selected, a city expends vast amounts of public revenue to begin a program of forced displacement, rental speculation, urban renewal, demolition of public housing and gentrification. In fact, if there is one thread that runs through almost every Olympic event it is that the poor of each subsidize their own violent dispossession. As money is pumped in to develop, regenerate and ‘clean’ the city, the surrounding community is forced to flee, transforming an urban collective identity into an individualized consumer one, defined by a narrow homogenized racial, economic and ethnic suburban ego ideal. This process of gentrification and suburbanization results in deep political and cultural insulation, alienation and detachment, detachment of families from one another, detachment from the commons. Detachment shapes the way individuals are exposed to and think about themselves in relation to the world, living a life of separation protected from ‘difference’. Passive acceptance of inequality is now actively espoused. The gentrification of the Olympic host city, the withering away of an urban working class, social atomization and the subsequent erosion of political consciousness is a planned outgrowth of a city seemingly waiting to be cleansed.

SUPPORTED BY HEROES LIKE YOU

Support independent eco journalism that drives real change.The Olympic legacy left behind reveals the motives of each host city. It is the necessity to shock, to fast track the dispossession of the poor and marginalized as part of the larger machinations of capital accumulation. The architects of this plan need a spectacular show; a hegemonic device to reconfigure the rights, spatial relations and self-determination of the city’s working class, to reconstitute for whom and for what purpose the city exists. Unlike any other event, the Olympics provide just that kind of opportunity.