Nature

Want to improve the world? - Slow down... and hear the science of kindness

- 25 min read

An interview with Graham Music author of The Good Life: Wellbeing and the new science of altruism, selfishness and immorality

An interview with Graham Music author of The Good Life: Wellbeing and the new science of altruism, selfishness and immorality

An interview with Graham Music by Louis Weinstock

Let me start with an obvious statement: if people were more kind, the world would be a better place. You don’t need to believe in unicorns, fairy-tales with happy endings, or supernatural deities to know this statement to be true. But given the undoubted importance of kindness, have you noticed just how little time we actually spend thinking about, talking about, or just doing kindness? Maybe kindness is too soft a subject to talk about in this all too serious world. Maybe we are more attracted to the darker side of human life. Most news reporting would certainly give you this impression. To delve deeper into the well of kindness, I interviewed Graham Music, a Consultant Child Psychotherapist, and author of a new book entitled “_The Good Life: Wellbeing and the new science of altruism, selfishness and immorality”._ In this mind-expanding, heart-opening book, Graham takes the reader on a journey through the history of human kindness, and its opposites like aggression, from our origins in tight-knit hunter-gatherer communities to the present day. He shares the very latest research on altruism, along with his decades of clinical experience, working with people who, often for similar reasons, really struggle to be kind. This gives him a very unique and illuminating perspective on what, if anything, turns kindness on and off. Louis: What prompted you to write this book?

Let me start with an obvious statement: if people were more kind, the world would be a better place. You don’t need to believe in unicorns, fairy-tales with happy endings, or supernatural deities to know this statement to be true. But given the undoubted importance of kindness, have you noticed just how little time we actually spend thinking about, talking about, or just doing kindness? Maybe kindness is too soft a subject to talk about in this all too serious world. Maybe we are more attracted to the darker side of human life. Most news reporting would certainly give you this impression. To delve deeper into the well of kindness, I interviewed Graham Music, a Consultant Child Psychotherapist, and author of a new book entitled “_The Good Life: Wellbeing and the new science of altruism, selfishness and immorality”._ In this mind-expanding, heart-opening book, Graham takes the reader on a journey through the history of human kindness, and its opposites like aggression, from our origins in tight-knit hunter-gatherer communities to the present day. He shares the very latest research on altruism, along with his decades of clinical experience, working with people who, often for similar reasons, really struggle to be kind. This gives him a very unique and illuminating perspective on what, if anything, turns kindness on and off. Louis: What prompted you to write this book?  Graham: I have worked for several decades with maltreated children, and adults who were severely abused as children. I had been noticing within myself that I was struggling to feel kindness towards some of these clients. Where I felt my heartstrings should have been pulled, because clients had really terrible things that had happened to them, their behaviours were actually making me feel less compassionate and more aversive to them. As a therapist, it was essential that I found a way of managing that discomfort inside of myself. Alongside that, I became fascinated with how my clients would become more kind when they began to take in good things from the world around them, be it from a good teacher, a good foster carer, mentor, or therapist. When these clients internalised a sense that the world could be a good place, it seemed to elicit something in them that allowed them to be more kind and more spontaneously generous, in a very unconscious way. So I started looking into this, and discovered loads of really interesting research which seemed to be showing that we humans are clearly born with altruistic tendencies. For example, babies as young as two months have been shown to have a profound moral sense, choosing goodies over baddies. As I absorbed this research, I came to realise that the severely maltreated children I was working with had literally had the goodness knocked out of them.

Graham: I have worked for several decades with maltreated children, and adults who were severely abused as children. I had been noticing within myself that I was struggling to feel kindness towards some of these clients. Where I felt my heartstrings should have been pulled, because clients had really terrible things that had happened to them, their behaviours were actually making me feel less compassionate and more aversive to them. As a therapist, it was essential that I found a way of managing that discomfort inside of myself. Alongside that, I became fascinated with how my clients would become more kind when they began to take in good things from the world around them, be it from a good teacher, a good foster carer, mentor, or therapist. When these clients internalised a sense that the world could be a good place, it seemed to elicit something in them that allowed them to be more kind and more spontaneously generous, in a very unconscious way. So I started looking into this, and discovered loads of really interesting research which seemed to be showing that we humans are clearly born with altruistic tendencies. For example, babies as young as two months have been shown to have a profound moral sense, choosing goodies over baddies. As I absorbed this research, I came to realise that the severely maltreated children I was working with had literally had the goodness knocked out of them. Louis: It seems like we humans absorb so much from the world around us, for better or worse. Is there a connection between our tendency to mimic and our altruistic behaviour? Graham: Yes, generally we like to be in tune with those around us and we like to feel understood. We tend to unconsciously mimic those we like or feel rapport with. This explains studies that show how waitresses who repeat back what has been ordered earn more tips than those who just say something positive. An infant only 20 minutes old will imitate many of the gestures of adults in front of them, most famously the sticking out of tongues. This isn’t just copying but shows a definite awareness of another’s feeling states and intentions. Infants do not imitate non-intentional gestures such as sneezing. We have all probably seen how infants resonate with those around them, smiling broadly in response to laughter, or looking sad when others are upset, as if they are mini barometers of people’s moods. These responses do not necessarily constitute a conscious awareness of other people’s feelings but do demonstrate sensitivity to them. So feeling good is partly a function of being in synchronous harmony with those around us. Louis: In your book, Nurturing Natures, you talk about some of the latest research that indicates our psyche is already being shaped, conditioned from early stages of gestation in the womb. Does this pre-natal conditioning also affect our capacity for altruism? Graham: Well, there is certainly programming already going on from the early days of gestation. We know for example that if a foetus hears a rhyme at 30 weeks, it will recognise that rhyme at 34 weeks. We know this because of experiments that have shown the foetus’ heart-rate increasing when it hears the same rhyme, indicating recognition. There are of course more negative psychological effects that take place in utero. For example, we know for sure that stress hormones cross the placenta and there is a very clear link in the research between stress levels and altruism. Louis: You talk a lot about this connection between stress and altruism in your book. It seems to be a key factor to be understood. Can you say more? Graham: Well, lets consider the evolutionary origins of our sympathetic nervous system. If a predator is coming around the corner, you are not very interested in how they are feeling. If you were, you wouldn't survive. Those fight, flight, freeze traits make utter evolutionary sense. We are very tense, suspicious, defensive in response to a threat, and in that state of mind we are not very responsive to other people’s thoughts or feelings. The parasympathetic nervous system, on the other hand, is the system linked with wellbeing. The core part of this system is the Smart Vagus nerve, which links with the heart, the stomach, brain stem, and facial muscles. When this system gets triggered, it functions as a ‘vagal break’, turning off sympathetic nervous reactions, so that we feel calmer, more at ease, we have an increased window of tolerance, and more of a hormone called oxytocin flows through the system. And this state of wellbeing is directly linked with a feeling of wanting to help people. Spontaneous altruism would often require us to be in this state. It is only in this state that we can be kind, generous in a really big-hearted way. It is important to recognise that some people can be kind in a more neurotic way (I suspect some therapists are like that), and this is a very different kind of kindness. One way of measuring vagal tone, is Heart Rate Variability (HRV). People who meditate a lot have incredibly high Heart Rate Variability. There is a term for such people, ‘vagal superstars’, coined by professor Dacher Keltener from Berkeley. These are people for whom very little phases them. The sort of clients that I see in therapy tend not to be vagal superstars, but rather have a very narrow window of tolerance. So, a big part of therapy and parenting and simply being a supportive human being is to gently catch someone just before they switch out of this window of tolerance, out of this smart vagal place, into sympathetic reactions, or dissociative reactions. When therapy goes well, we are catching our clients before they switch out of the super-vagal state, and so we are expanding their window of tolerance. Louis: Is there an evolutionary reason why we evolved this parasympathetic vagal system? Why might this altruistic cooperative system have developed, from an evolutionary point of view?

Louis: It seems like we humans absorb so much from the world around us, for better or worse. Is there a connection between our tendency to mimic and our altruistic behaviour? Graham: Yes, generally we like to be in tune with those around us and we like to feel understood. We tend to unconsciously mimic those we like or feel rapport with. This explains studies that show how waitresses who repeat back what has been ordered earn more tips than those who just say something positive. An infant only 20 minutes old will imitate many of the gestures of adults in front of them, most famously the sticking out of tongues. This isn’t just copying but shows a definite awareness of another’s feeling states and intentions. Infants do not imitate non-intentional gestures such as sneezing. We have all probably seen how infants resonate with those around them, smiling broadly in response to laughter, or looking sad when others are upset, as if they are mini barometers of people’s moods. These responses do not necessarily constitute a conscious awareness of other people’s feelings but do demonstrate sensitivity to them. So feeling good is partly a function of being in synchronous harmony with those around us. Louis: In your book, Nurturing Natures, you talk about some of the latest research that indicates our psyche is already being shaped, conditioned from early stages of gestation in the womb. Does this pre-natal conditioning also affect our capacity for altruism? Graham: Well, there is certainly programming already going on from the early days of gestation. We know for example that if a foetus hears a rhyme at 30 weeks, it will recognise that rhyme at 34 weeks. We know this because of experiments that have shown the foetus’ heart-rate increasing when it hears the same rhyme, indicating recognition. There are of course more negative psychological effects that take place in utero. For example, we know for sure that stress hormones cross the placenta and there is a very clear link in the research between stress levels and altruism. Louis: You talk a lot about this connection between stress and altruism in your book. It seems to be a key factor to be understood. Can you say more? Graham: Well, lets consider the evolutionary origins of our sympathetic nervous system. If a predator is coming around the corner, you are not very interested in how they are feeling. If you were, you wouldn't survive. Those fight, flight, freeze traits make utter evolutionary sense. We are very tense, suspicious, defensive in response to a threat, and in that state of mind we are not very responsive to other people’s thoughts or feelings. The parasympathetic nervous system, on the other hand, is the system linked with wellbeing. The core part of this system is the Smart Vagus nerve, which links with the heart, the stomach, brain stem, and facial muscles. When this system gets triggered, it functions as a ‘vagal break’, turning off sympathetic nervous reactions, so that we feel calmer, more at ease, we have an increased window of tolerance, and more of a hormone called oxytocin flows through the system. And this state of wellbeing is directly linked with a feeling of wanting to help people. Spontaneous altruism would often require us to be in this state. It is only in this state that we can be kind, generous in a really big-hearted way. It is important to recognise that some people can be kind in a more neurotic way (I suspect some therapists are like that), and this is a very different kind of kindness. One way of measuring vagal tone, is Heart Rate Variability (HRV). People who meditate a lot have incredibly high Heart Rate Variability. There is a term for such people, ‘vagal superstars’, coined by professor Dacher Keltener from Berkeley. These are people for whom very little phases them. The sort of clients that I see in therapy tend not to be vagal superstars, but rather have a very narrow window of tolerance. So, a big part of therapy and parenting and simply being a supportive human being is to gently catch someone just before they switch out of this window of tolerance, out of this smart vagal place, into sympathetic reactions, or dissociative reactions. When therapy goes well, we are catching our clients before they switch out of the super-vagal state, and so we are expanding their window of tolerance. Louis: Is there an evolutionary reason why we evolved this parasympathetic vagal system? Why might this altruistic cooperative system have developed, from an evolutionary point of view?  Graham: We human beings are a group species. A significant stage in our evolutionary journey took place some 40-50000 years ago, when we started living in small hunter-gatherer communities. In these small communities, the evidence suggests that we were very cooperative, very closely bonded. In fact, group-life demanded high levels of trust. If you were individualistic or selfish, if you didn't cooperate, you would be mercilessly teased, ostracised, or kicked out. On the other hand, if you did cooperate, you would be more likely to mate and pass on these traits, and more likely to survive in these environments. Closely-knit groups survived the conditions of those times. This is the evolutionary phenomenon of group-level selection, where the strongest groups survive. In fact, studies of hunter-gatherer communities, in whatever environment, from the Arctic to the Sahara, show that these groups all had very similar forms of social organisation. There is so much research today that says it is better for us to be part of social groups: we are more likely to survive cancer, we are more likely to survive strokes. Community life is literally health-enhancing. So it is not surprising when we hear of experiments such as Michael Tomasello’s, where toddlers helped others simply because they found helping rewarding, but actually tended to help less if the reward was extrinsic, say sweets or another treat. There is a big physiological link to this altruistic community life, which is the bonding hormone oxytocin. When oxytocin is given to people artificially, they become more loving, more interested in other people's feelings. A very good example of oxytocin’s effects in the natural world is taken from the world of voles. There is a type of vole called the prairie vole. These voles operate in a similar way to humans: they bond for life, they share parental roles, and build nests in an egalitarian way, in couples. Monogamous prairie voles are known to have higher levels of receptors for Oxytocin than their more promiscuous counterparts, the Montane voles. Montane voles, on the other hand, are more feckless, and as soon as they have impregnated their mate, they run off to find another mate. However, studies have shown that when these promiscuous voles are dosed with oxytocin, they adopt the monogamous behaviour of their prairie cousins. Louis: So there seems to be a very real connection between long-term bonds, commitment to close ones, and oxytocin? Graham: Well they say love is blind, because you can’t see people's faults. But yes, maybe this blindness is necessary to enhance group survival. The downside of oxytocin, is that when people are given oxytocin, they have tended to favour their own group even more above another group. So, if I was given a boost of oxytocin, this could lead me to prefer my group (let’s say of Tavistock trained psycotherapists) over your group (CCPE trained psychotherapists). Louis: In your book you talk about the current state of the world, and the sense you have that we might be moving dangerously away from altruism. Can you say more about that? Graham: It seems to me that in the modern Western world, society is set up in such a way as to favour more selfish, more psychopathic tendencies. If you are calculated, tough, insensitive, you can make a lot of money and be very powerful. The sorts of checks and balances against individualism that exist in small groups do not seem to carry the same weight in larger groups. In the financial realm, bankers gaining massive bonuses are far less visible and harder to shame than a hunter-gatherer who takes most of the spoils of a hunt. Unlike in hunter-gatherer societies, people cannot take the law into their own hands to protest and dispense justice when acts that are deemed wrong are in fact legal, whether tax evasion, the exploitation of fish stocks, industrial emissions, environmental pollution or indeed the increasing inequality in Western societies. The law often protects those who gain from such acts.

Graham: We human beings are a group species. A significant stage in our evolutionary journey took place some 40-50000 years ago, when we started living in small hunter-gatherer communities. In these small communities, the evidence suggests that we were very cooperative, very closely bonded. In fact, group-life demanded high levels of trust. If you were individualistic or selfish, if you didn't cooperate, you would be mercilessly teased, ostracised, or kicked out. On the other hand, if you did cooperate, you would be more likely to mate and pass on these traits, and more likely to survive in these environments. Closely-knit groups survived the conditions of those times. This is the evolutionary phenomenon of group-level selection, where the strongest groups survive. In fact, studies of hunter-gatherer communities, in whatever environment, from the Arctic to the Sahara, show that these groups all had very similar forms of social organisation. There is so much research today that says it is better for us to be part of social groups: we are more likely to survive cancer, we are more likely to survive strokes. Community life is literally health-enhancing. So it is not surprising when we hear of experiments such as Michael Tomasello’s, where toddlers helped others simply because they found helping rewarding, but actually tended to help less if the reward was extrinsic, say sweets or another treat. There is a big physiological link to this altruistic community life, which is the bonding hormone oxytocin. When oxytocin is given to people artificially, they become more loving, more interested in other people's feelings. A very good example of oxytocin’s effects in the natural world is taken from the world of voles. There is a type of vole called the prairie vole. These voles operate in a similar way to humans: they bond for life, they share parental roles, and build nests in an egalitarian way, in couples. Monogamous prairie voles are known to have higher levels of receptors for Oxytocin than their more promiscuous counterparts, the Montane voles. Montane voles, on the other hand, are more feckless, and as soon as they have impregnated their mate, they run off to find another mate. However, studies have shown that when these promiscuous voles are dosed with oxytocin, they adopt the monogamous behaviour of their prairie cousins. Louis: So there seems to be a very real connection between long-term bonds, commitment to close ones, and oxytocin? Graham: Well they say love is blind, because you can’t see people's faults. But yes, maybe this blindness is necessary to enhance group survival. The downside of oxytocin, is that when people are given oxytocin, they have tended to favour their own group even more above another group. So, if I was given a boost of oxytocin, this could lead me to prefer my group (let’s say of Tavistock trained psycotherapists) over your group (CCPE trained psychotherapists). Louis: In your book you talk about the current state of the world, and the sense you have that we might be moving dangerously away from altruism. Can you say more about that? Graham: It seems to me that in the modern Western world, society is set up in such a way as to favour more selfish, more psychopathic tendencies. If you are calculated, tough, insensitive, you can make a lot of money and be very powerful. The sorts of checks and balances against individualism that exist in small groups do not seem to carry the same weight in larger groups. In the financial realm, bankers gaining massive bonuses are far less visible and harder to shame than a hunter-gatherer who takes most of the spoils of a hunt. Unlike in hunter-gatherer societies, people cannot take the law into their own hands to protest and dispense justice when acts that are deemed wrong are in fact legal, whether tax evasion, the exploitation of fish stocks, industrial emissions, environmental pollution or indeed the increasing inequality in Western societies. The law often protects those who gain from such acts.  Louis: I recently watched a documentary about Donald Rumsfeld called 'The Unknown Known'. Donald has been one of the most powerful men in recent history, at the helm for decisions that have triggered a series of wars going all the way back to Vietnam. I was struck in this film by how Donald was so incredibly logical, so clear-thinking, so rational. It was almost scary. When he describes in this documentary his early negotiations with Saddam Huseein and Tariq Aziz, he says that negotiations failed because ‘_these people would just not listen to reason_’. It seems that the West has been planning and executing its interventions in the world at least partly on the basis of the power of reason, which must triumph ultimately. Do you think this faith in reason is problematic? Graham: To understand this, we need to understand a bit about the brain. The right brain is dominant for sustained, broad, and open states of mind related to connecting with the world and with others, whilst the left-brain is dominant for narrow, sharply-focused attention to details. In the West it seems that we have moved towards a left-brain dominated world. The left-brain is hopeless at uncertainty, it needs to fit everything into a system and won't brook any disagreement. Someone like Donald Rumsfeld typifies the shift to the left-hemisphere, towards sharply-focused attention to details, and to the systematic classification of uncertainty. Interestingly, Iain McGilchrist, in his seminal book on the brain ‘The Master and his Emissary’, says that one of the few emotions that tends to be dominant in the left hemisphere is anger. People like Donald Rumsfeld tend to express the emotion of anger quite freely if someone disagrees with them.

Louis: I recently watched a documentary about Donald Rumsfeld called 'The Unknown Known'. Donald has been one of the most powerful men in recent history, at the helm for decisions that have triggered a series of wars going all the way back to Vietnam. I was struck in this film by how Donald was so incredibly logical, so clear-thinking, so rational. It was almost scary. When he describes in this documentary his early negotiations with Saddam Huseein and Tariq Aziz, he says that negotiations failed because ‘_these people would just not listen to reason_’. It seems that the West has been planning and executing its interventions in the world at least partly on the basis of the power of reason, which must triumph ultimately. Do you think this faith in reason is problematic? Graham: To understand this, we need to understand a bit about the brain. The right brain is dominant for sustained, broad, and open states of mind related to connecting with the world and with others, whilst the left-brain is dominant for narrow, sharply-focused attention to details. In the West it seems that we have moved towards a left-brain dominated world. The left-brain is hopeless at uncertainty, it needs to fit everything into a system and won't brook any disagreement. Someone like Donald Rumsfeld typifies the shift to the left-hemisphere, towards sharply-focused attention to details, and to the systematic classification of uncertainty. Interestingly, Iain McGilchrist, in his seminal book on the brain ‘The Master and his Emissary’, says that one of the few emotions that tends to be dominant in the left hemisphere is anger. People like Donald Rumsfeld tend to express the emotion of anger quite freely if someone disagrees with them.  We see similar traits in psychopaths. Psychopaths have poor links between limbic areas of the brain and the pre-frontal areas. Psychopaths are not able to listen to their own emotional signalling. So they tend to respond very rationally to a situation, but they just can not trust information they are getting through any other means than logical information. People who have had brain damage to the pre-frontal cortex have similar problems. They can not trust their intuition or their emotional signalling. Louis: That is really interesting. Is there a connection then between the world of addictions and being cut off from the more intuitive, emotional parts of our selves? Graham: Well, there is definitely some emotional signalling going on in addictions. In fact, the potentially addictive part of our personality developed for very good evolutionary reasons. Dopamine is the hormone involved in a lot of addictions, and it is the hormone that drives us towards goals. From an evolutionary point of view, we need to be driven towards things so that we can procreate and ensure our survival. It is not surprising that there is a huge sense of reward and pleasure which encourages us to keep moving towards sex. Conversely, very depressed mothers tend to have very low dopamine. But the key thing about dopamine is that the dopamine system seems to drive us to go for the thing, more than the pleasure received when one has got the thing one is after. It seems like we are living in a society that is dopamine driven. We are driven towards new objects all the time. We really want that new iPhone, but we don't feel that good when we get it. This dopamine-oriented seeking is a very hedonistic and superficial drive. This does not represent wellbeing in the sense of a deeper, more sustained fulfilment: what Aristotle means by eudaimonia.

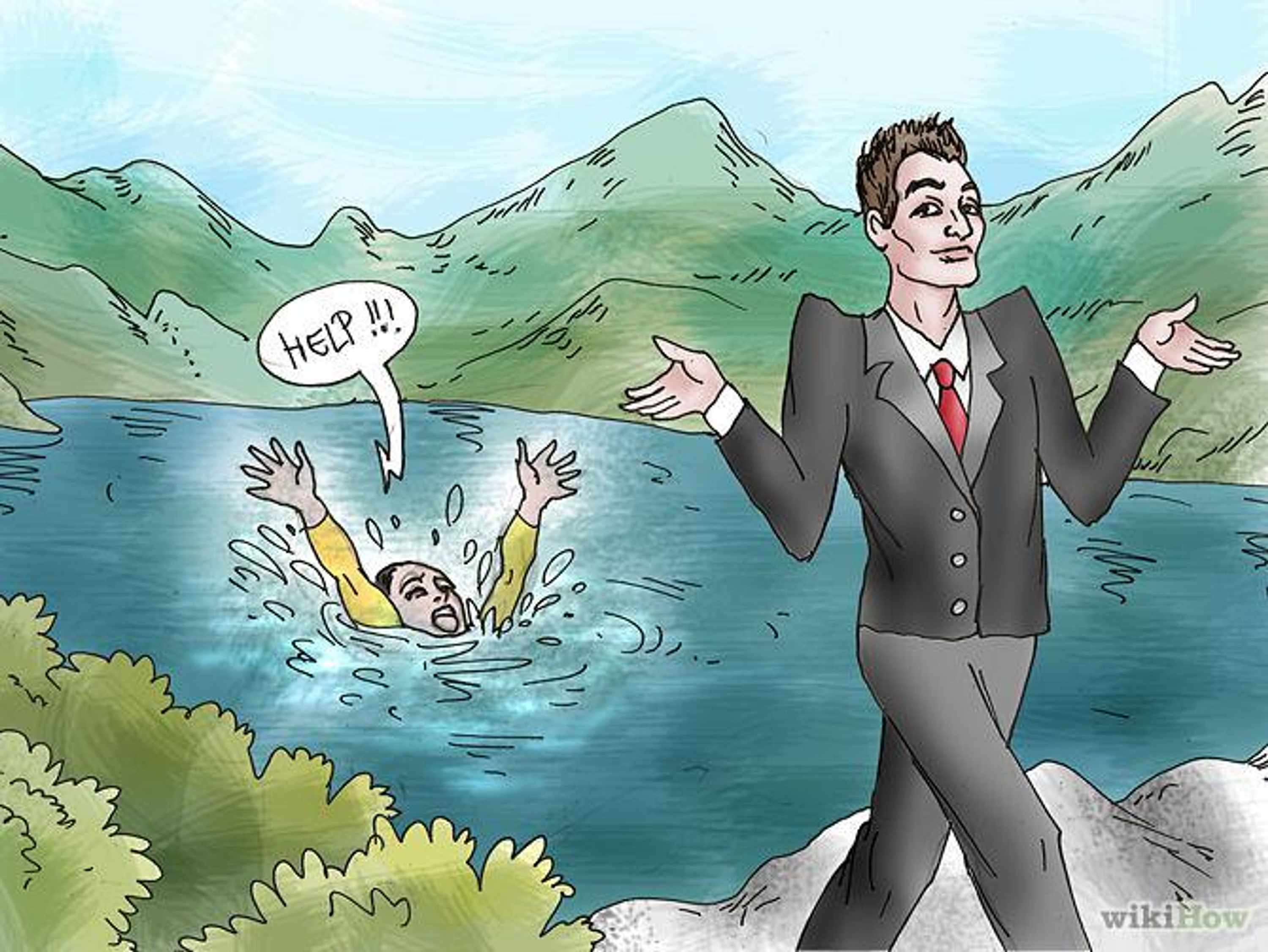

We see similar traits in psychopaths. Psychopaths have poor links between limbic areas of the brain and the pre-frontal areas. Psychopaths are not able to listen to their own emotional signalling. So they tend to respond very rationally to a situation, but they just can not trust information they are getting through any other means than logical information. People who have had brain damage to the pre-frontal cortex have similar problems. They can not trust their intuition or their emotional signalling. Louis: That is really interesting. Is there a connection then between the world of addictions and being cut off from the more intuitive, emotional parts of our selves? Graham: Well, there is definitely some emotional signalling going on in addictions. In fact, the potentially addictive part of our personality developed for very good evolutionary reasons. Dopamine is the hormone involved in a lot of addictions, and it is the hormone that drives us towards goals. From an evolutionary point of view, we need to be driven towards things so that we can procreate and ensure our survival. It is not surprising that there is a huge sense of reward and pleasure which encourages us to keep moving towards sex. Conversely, very depressed mothers tend to have very low dopamine. But the key thing about dopamine is that the dopamine system seems to drive us to go for the thing, more than the pleasure received when one has got the thing one is after. It seems like we are living in a society that is dopamine driven. We are driven towards new objects all the time. We really want that new iPhone, but we don't feel that good when we get it. This dopamine-oriented seeking is a very hedonistic and superficial drive. This does not represent wellbeing in the sense of a deeper, more sustained fulfilment: what Aristotle means by eudaimonia.  And the difference between these two types of pleasure is very much linked with the difference between extrinsic and intrinsic rewards. More insecure kids often feel the need to look immaculate, to have the latest trainers, to desperately want to be famous. These are very extrinsic ambitions. Whereas, the emotional health we therapists are aiming for with clients would be a feeling good about yourself regardless of these exterior perceptions and drives. And most interestingly, although perhaps not surprisingly, people with extrinsic motivations are much less likely to be kind, less likely to be generous, less likely to be interested in other people. These extrinsically motivated types of people are much more likely to be driven by dopamine. Louis: What I found fascinating as a drugs-counsellor was how crack addicts would spend hundreds and thousands of pounds a day on a drug, constantly risking their lives to get the resources to obtain the drugs, and yet when I asked them what effect the drug had on them, they would often shrug their shoulders and say ‘hardly anything’. It seems we are at risk of becoming drones, robotically driven back to the same objects, even though they have stopped bringing us pleasure. This seems like insanity. Is there some kind of cut-off between learning and reality? Graham: We know that we humans are not very good at unlearning what we have learnt early on. One key factor that helps us in our learning is finding that still-point from which we can retain some freedom in our responses. Viktor Frankl, the psychiatrist who survived a concentration camp during the Holocaust, talks about the possibility of freedom arising when we can create a gap between stimulus and response. And that is really at bottom what mindfulness and psychotherapy is all about. It is also key to recognise the link between our stress levels and addictions. We know that if you stick a pile of cocaine in front of a load of rats, or monkeys for that matter, then it is the stressed ones who will keep going back to the cocaine. The stressed ones keep going back because they are compensating for something they instinctively sense they are lacking. And in this consumerist society, we are constantly being told that we are lacking something, so our primitive drives towards objects are being manipulated. In James Roberts’ book, Shiny Objects, he describes how urges and desires for material things become addictive in their own right, indeed in a similar way to that which occurs in some forms of addiction. And these days it is becoming easier and easier to buy stuff. You can attain the object of your desire at the click of a button nowadays. But of course, these purchases rarely help us feel better about our lives. I used to be an antique dealer. I remember going to the antiques market and having this excited sense of "I’m going to find something amazing today”. Of course, I rarely did find something that matched the magnitude of my desires, and even if I did find something special, the pleasure was never that great, and I soon wanted to move onto the next thing. So, it is really crucial that we understand how extrinsic ways of relating are really bad for our mental health. There is a tonne of research that demonstrates how people who are extrinsically motivated have worse mental health, almost across the board. There is another fascinating experiment which shows how certain factors in the extrinsic world can affect in a surprising and subtle way how we act. Subjects were given words to rearrange into sentences. Some had in front of them a random selection of words whereas others had similar ones but also some words linked with finance such as ‘profit’ or ‘high salary’. After this task they had a more complex puzzle to do, and they could both ask for help, and also offer help. Those who compiled sentences using the financial words took about five minutes longer to ask for help and were also less likely to offer help. Being primed with financial words prods people to act more selfishly and self-reliantly. Presumably more consumerist and money-oriented cultures and influences would have a different effect on moral behaviours to more altruistic or spiritual societies. Louis: What advice would you give to a parent who wants to bring up a child that is altruistic and more intrinsically motivated? Graham: I would tell them to love their children as unconditionally as they can, without making them narcissistic. It is of course essential to have some boundaries. But it is equally important that children are encouraged to trust in themselves. Some people have argued convincingly that we are not well adapted as a species to aspects of modern life, and in particular modern childcare methods. There is a whole tranche of developmental outcomes that we equate with psychological health which are also closely associated with forms of childrearing consistently seen in communities closer to the hunter-gatherer model, but less so in contemporary societies. These include being held or very near others constantly, prompt attuned responses to signs of distress or upset, breast-feeding more or less on demand for the first years, co-sleeping, having several known alternative caregivers in addition to parents, high levels of social embeddedness and a lot of free-play with children of a range of ages. Such an approach to childrearing is strongly correlated with outcomes such as higher levels of empathy and emotional recognition, better emotional regulation and less impulsiveness, for example. These traditional forms of parenting can be very difficult in a world in which we value external achievements so highly. Its very hard as a parent to not get over motivated by how their children have done in exams, how they compare to their peers. There is so much extrinsic pressure around for children to conform to a modern social ideal. Don’t take them to structured activity time all the time. Allow them to trust the symbolic world inside of themselves. You do need some stimulation. It is important to place things before your child in which can help their development, as long as the child is driven toward that thing by something inside of themself. If this happens, your child will be naturally be more curious and more interested in other people and in life. In terms of altruism, spontaneous altruism will emerge under intrinsically motivated conditions. But kids will also learn about kindness by having kindness done to them. Kids who have been abused are not as kind to other kids. They don’t help or offer sympathy as much . The kids who are more securely attached often become good friends. They have the flexbility to move gracefully between different moods. Louis: This whole business of remaining intrinsic seems anathema to the way modern society is set up. In my own therapy practice, I always seek to empower the client to find solutions within themselves. But I am noticing more and more that people want somebody outside of themselves to just ‘fix them’. Is this a modern trend? Graham: Well I suspect that people have always wanted somebody outside of themselves to fix them, but there is definitely much more of a culture of that now. We live in a world where people expect quick fixes. So, if people have a sense of suffering, they want somebody to provide them with a quick fix. If you have attention-problems, we’ll give you Ritalin, rather than looking at the deeper problems the attention-deficit represents. Learning to bear and stay with emotions rather than trying to get rid of them is a fundamental part of a rich life, a life worth living. But in the age of the quick fix, where companies like Google earn more money the more clicks they get, there is a massive incentive to keep us clicking, so that we never stay with anything very long, we are always jumping around. Even for my generation that grew up a long long time before the internet was born, even our brains are changing as a result of this quick-fix, push-of-a-button world. Recent research has shown that regular internet users who were over 55, for example, had far more activity in left prefrontal brain areas than less internet-savvy people, and that just a few weeks of intensive internet usage changed these brain patterns in novices as well. Louis: What advice would you give to someone who genuinely wants the world to be a better place? If the reader genuinely wishes for the world to be a more altruistic, a more caring place, what kind of things could they be doing? Graham: Apart from having a revolution?! Making sure the economy is not just ruled by profit motive seems to be hugely important, as this drives us away from our altruistic nature. Neoliberalism is having a shocking effect on downgrading wages, and making the world in which we live more 24/7, and much more insecure. All these things conspire to make us more short-term in our thinking. They also make us more stressed, and so our altruistic traits are turned offline, as we become more extrinsically motivated. Tim Kasser has done some really interesting research, where he showed that intrinsically motivated people are far more likely to be environmentally aware than extrinsically motivated people. So when we are intrinsically motivated, our altruism extends well beyond our group. What is really key for society to become more altruistic is that we need two things. First, we need people to be made more fully and deeply aware of the dangers of where we are headed as a species. Study after study has shown that humans have an ‘optimism bias’. We avoid believing the worst, a strategy that has often served us well over our evolutionary history, but maybe not now when our problems are global, and disasters threaten. We need to know just how dangerous the situation is if we are to feel sufficient urgency to make sacrifices for a cause. Second, we need to put pressure on society to value and promote good parenting. We know that programming in the first couple of years will make a huge difference. So, we need as a society to put far greater emotional resources into the early years of parenting, and this includes whilst mothers are pregnant. If we can provide these structures, then we will have a society where people are developing brains, bodies, hormonal systems that allow us to be more open, more interested, more caring. To put it bluntly, you are far less likely to care about saving the environment if as a child you have not been neglected or abused or simply not shown how to care. Louis: Finally, there are two classic experiments you talk about in your book that really beautifully capture the essence of altruism. I think one is called the dime experiment, and the other the good samaritan experiment. Can you say more about these experiments and what they reveal about our nature? Graham: Well, in the dime experiment, a dime was sometimes left in a phone booth and at other times no money was left. Random people were observed using these phone booths, and as they came out, an actress pretended to drop a sheaf of paper. Fascinatingly, over 80 per cent of the people who had unexpectedly found a dime helped the person who supposedly had dropped the papers, while less than 10 per cent of those who did not find a dime offered to help. Of course a dime was a very insignificant amount of money even in 1972. But what this experiment shows is that, when the world feels like a more beneficent place, we tend to respond more kindly to others. In the other experiment, theology students were instructed that they had to give a talk in a nearby hall. Some were then told they had to hurry as the talk was very soon, whilst others were told that they had plenty of time. Also some were instructed to give their talk about the parable of the Good Samaritan, while others talked about a non-helping topic. An actor told to look like he was in trouble was positioned en route to the talk. Normally, being primed with the Good Samaritan story would increase the likelihood of any of us offering help to someone in distress, and presumably theology students even more so. Interestingly though, of those in a hurry, only 10 per cent stopped, as opposed to 63 per cent who had more time, irrespective of the talk they were to give. Stress, busyness and anxiety, even in small doses, makes us less caring and less other-minded. Chronic levels of stress have an even worse effect.

And the difference between these two types of pleasure is very much linked with the difference between extrinsic and intrinsic rewards. More insecure kids often feel the need to look immaculate, to have the latest trainers, to desperately want to be famous. These are very extrinsic ambitions. Whereas, the emotional health we therapists are aiming for with clients would be a feeling good about yourself regardless of these exterior perceptions and drives. And most interestingly, although perhaps not surprisingly, people with extrinsic motivations are much less likely to be kind, less likely to be generous, less likely to be interested in other people. These extrinsically motivated types of people are much more likely to be driven by dopamine. Louis: What I found fascinating as a drugs-counsellor was how crack addicts would spend hundreds and thousands of pounds a day on a drug, constantly risking their lives to get the resources to obtain the drugs, and yet when I asked them what effect the drug had on them, they would often shrug their shoulders and say ‘hardly anything’. It seems we are at risk of becoming drones, robotically driven back to the same objects, even though they have stopped bringing us pleasure. This seems like insanity. Is there some kind of cut-off between learning and reality? Graham: We know that we humans are not very good at unlearning what we have learnt early on. One key factor that helps us in our learning is finding that still-point from which we can retain some freedom in our responses. Viktor Frankl, the psychiatrist who survived a concentration camp during the Holocaust, talks about the possibility of freedom arising when we can create a gap between stimulus and response. And that is really at bottom what mindfulness and psychotherapy is all about. It is also key to recognise the link between our stress levels and addictions. We know that if you stick a pile of cocaine in front of a load of rats, or monkeys for that matter, then it is the stressed ones who will keep going back to the cocaine. The stressed ones keep going back because they are compensating for something they instinctively sense they are lacking. And in this consumerist society, we are constantly being told that we are lacking something, so our primitive drives towards objects are being manipulated. In James Roberts’ book, Shiny Objects, he describes how urges and desires for material things become addictive in their own right, indeed in a similar way to that which occurs in some forms of addiction. And these days it is becoming easier and easier to buy stuff. You can attain the object of your desire at the click of a button nowadays. But of course, these purchases rarely help us feel better about our lives. I used to be an antique dealer. I remember going to the antiques market and having this excited sense of "I’m going to find something amazing today”. Of course, I rarely did find something that matched the magnitude of my desires, and even if I did find something special, the pleasure was never that great, and I soon wanted to move onto the next thing. So, it is really crucial that we understand how extrinsic ways of relating are really bad for our mental health. There is a tonne of research that demonstrates how people who are extrinsically motivated have worse mental health, almost across the board. There is another fascinating experiment which shows how certain factors in the extrinsic world can affect in a surprising and subtle way how we act. Subjects were given words to rearrange into sentences. Some had in front of them a random selection of words whereas others had similar ones but also some words linked with finance such as ‘profit’ or ‘high salary’. After this task they had a more complex puzzle to do, and they could both ask for help, and also offer help. Those who compiled sentences using the financial words took about five minutes longer to ask for help and were also less likely to offer help. Being primed with financial words prods people to act more selfishly and self-reliantly. Presumably more consumerist and money-oriented cultures and influences would have a different effect on moral behaviours to more altruistic or spiritual societies. Louis: What advice would you give to a parent who wants to bring up a child that is altruistic and more intrinsically motivated? Graham: I would tell them to love their children as unconditionally as they can, without making them narcissistic. It is of course essential to have some boundaries. But it is equally important that children are encouraged to trust in themselves. Some people have argued convincingly that we are not well adapted as a species to aspects of modern life, and in particular modern childcare methods. There is a whole tranche of developmental outcomes that we equate with psychological health which are also closely associated with forms of childrearing consistently seen in communities closer to the hunter-gatherer model, but less so in contemporary societies. These include being held or very near others constantly, prompt attuned responses to signs of distress or upset, breast-feeding more or less on demand for the first years, co-sleeping, having several known alternative caregivers in addition to parents, high levels of social embeddedness and a lot of free-play with children of a range of ages. Such an approach to childrearing is strongly correlated with outcomes such as higher levels of empathy and emotional recognition, better emotional regulation and less impulsiveness, for example. These traditional forms of parenting can be very difficult in a world in which we value external achievements so highly. Its very hard as a parent to not get over motivated by how their children have done in exams, how they compare to their peers. There is so much extrinsic pressure around for children to conform to a modern social ideal. Don’t take them to structured activity time all the time. Allow them to trust the symbolic world inside of themselves. You do need some stimulation. It is important to place things before your child in which can help their development, as long as the child is driven toward that thing by something inside of themself. If this happens, your child will be naturally be more curious and more interested in other people and in life. In terms of altruism, spontaneous altruism will emerge under intrinsically motivated conditions. But kids will also learn about kindness by having kindness done to them. Kids who have been abused are not as kind to other kids. They don’t help or offer sympathy as much . The kids who are more securely attached often become good friends. They have the flexbility to move gracefully between different moods. Louis: This whole business of remaining intrinsic seems anathema to the way modern society is set up. In my own therapy practice, I always seek to empower the client to find solutions within themselves. But I am noticing more and more that people want somebody outside of themselves to just ‘fix them’. Is this a modern trend? Graham: Well I suspect that people have always wanted somebody outside of themselves to fix them, but there is definitely much more of a culture of that now. We live in a world where people expect quick fixes. So, if people have a sense of suffering, they want somebody to provide them with a quick fix. If you have attention-problems, we’ll give you Ritalin, rather than looking at the deeper problems the attention-deficit represents. Learning to bear and stay with emotions rather than trying to get rid of them is a fundamental part of a rich life, a life worth living. But in the age of the quick fix, where companies like Google earn more money the more clicks they get, there is a massive incentive to keep us clicking, so that we never stay with anything very long, we are always jumping around. Even for my generation that grew up a long long time before the internet was born, even our brains are changing as a result of this quick-fix, push-of-a-button world. Recent research has shown that regular internet users who were over 55, for example, had far more activity in left prefrontal brain areas than less internet-savvy people, and that just a few weeks of intensive internet usage changed these brain patterns in novices as well. Louis: What advice would you give to someone who genuinely wants the world to be a better place? If the reader genuinely wishes for the world to be a more altruistic, a more caring place, what kind of things could they be doing? Graham: Apart from having a revolution?! Making sure the economy is not just ruled by profit motive seems to be hugely important, as this drives us away from our altruistic nature. Neoliberalism is having a shocking effect on downgrading wages, and making the world in which we live more 24/7, and much more insecure. All these things conspire to make us more short-term in our thinking. They also make us more stressed, and so our altruistic traits are turned offline, as we become more extrinsically motivated. Tim Kasser has done some really interesting research, where he showed that intrinsically motivated people are far more likely to be environmentally aware than extrinsically motivated people. So when we are intrinsically motivated, our altruism extends well beyond our group. What is really key for society to become more altruistic is that we need two things. First, we need people to be made more fully and deeply aware of the dangers of where we are headed as a species. Study after study has shown that humans have an ‘optimism bias’. We avoid believing the worst, a strategy that has often served us well over our evolutionary history, but maybe not now when our problems are global, and disasters threaten. We need to know just how dangerous the situation is if we are to feel sufficient urgency to make sacrifices for a cause. Second, we need to put pressure on society to value and promote good parenting. We know that programming in the first couple of years will make a huge difference. So, we need as a society to put far greater emotional resources into the early years of parenting, and this includes whilst mothers are pregnant. If we can provide these structures, then we will have a society where people are developing brains, bodies, hormonal systems that allow us to be more open, more interested, more caring. To put it bluntly, you are far less likely to care about saving the environment if as a child you have not been neglected or abused or simply not shown how to care. Louis: Finally, there are two classic experiments you talk about in your book that really beautifully capture the essence of altruism. I think one is called the dime experiment, and the other the good samaritan experiment. Can you say more about these experiments and what they reveal about our nature? Graham: Well, in the dime experiment, a dime was sometimes left in a phone booth and at other times no money was left. Random people were observed using these phone booths, and as they came out, an actress pretended to drop a sheaf of paper. Fascinatingly, over 80 per cent of the people who had unexpectedly found a dime helped the person who supposedly had dropped the papers, while less than 10 per cent of those who did not find a dime offered to help. Of course a dime was a very insignificant amount of money even in 1972. But what this experiment shows is that, when the world feels like a more beneficent place, we tend to respond more kindly to others. In the other experiment, theology students were instructed that they had to give a talk in a nearby hall. Some were then told they had to hurry as the talk was very soon, whilst others were told that they had plenty of time. Also some were instructed to give their talk about the parable of the Good Samaritan, while others talked about a non-helping topic. An actor told to look like he was in trouble was positioned en route to the talk. Normally, being primed with the Good Samaritan story would increase the likelihood of any of us offering help to someone in distress, and presumably theology students even more so. Interestingly though, of those in a hurry, only 10 per cent stopped, as opposed to 63 per cent who had more time, irrespective of the talk they were to give. Stress, busyness and anxiety, even in small doses, makes us less caring and less other-minded. Chronic levels of stress have an even worse effect. So, our potential for kindness is being killed off by a society in which we are all in a rush. If we can find a way to help people slow down, we can really help to connect people to their altruistic selves. This not only is better for society, but we also know that being generous, caring, and kind helps the giver as much as the receiver. Being altruistic improves our physical and mental health. Based on what we now know, it is a huge responsibility we all have, to make sure we don’t rush around ourselves, and to make sure we are kind to other people. Of course, we all slip in and out of those states. I can be as nasty as the next person. The key thing is that we recognise that altruism is part of our evolutionary heritage, and so we need to create a society that supports our natural tendencies to be kind to one another. ---------

So, our potential for kindness is being killed off by a society in which we are all in a rush. If we can find a way to help people slow down, we can really help to connect people to their altruistic selves. This not only is better for society, but we also know that being generous, caring, and kind helps the giver as much as the receiver. Being altruistic improves our physical and mental health. Based on what we now know, it is a huge responsibility we all have, to make sure we don’t rush around ourselves, and to make sure we are kind to other people. Of course, we all slip in and out of those states. I can be as nasty as the next person. The key thing is that we recognise that altruism is part of our evolutionary heritage, and so we need to create a society that supports our natural tendencies to be kind to one another. ---------

Interview by Louis Weinstock

'Louis is a Psychotherapist, Wellbeing Consultant, and Founder of A Quiet Evolution, psychotherapy service for children and grown-ups, and co-founder of Wisdom Connects, an international youth wisdom project. Louis brings heart and wisdom to those in acute need. He helped Kids Company design and run a therapeutic education provision for vulnerable teenagers, and consulted Headspace on a mindfulness app for kids. Louis runs a meditation group, Conscious In London, and organises culture-jamming, love-spreading events.'

'Louis is a Psychotherapist, Wellbeing Consultant, and Founder of A Quiet Evolution, psychotherapy service for children and grown-ups, and co-founder of Wisdom Connects, an international youth wisdom project. Louis brings heart and wisdom to those in acute need. He helped Kids Company design and run a therapeutic education provision for vulnerable teenagers, and consulted Headspace on a mindfulness app for kids. Louis runs a meditation group, Conscious In London, and organises culture-jamming, love-spreading events.'

For more information on Graham Music see:

Featured image by: Tamara Phillips :: the art of coloured water www.TamaraPhillips.ca www.facebook.com/TamaraPhillipsArt www.etsy.com/shop/DeepColouredWater [caption id="attachment_6922" align="aligncenter" width="748"] Image credit: www.TamaraPhillips.ca\[/caption\]

Image credit: www.TamaraPhillips.ca\[/caption\]