Technology

Delay tactics - when will the salmon industry clean up its act?

- 12 min read

Sector’s economic benefits exaggerated and a broad alliance of experts still sound the alarm over environmental impacts

Sector’s economic benefits exaggerated and a broad alliance of experts still sound the alarm over environmental impacts

“The status quo is not an option.” This was the conclusion of two independent inquiries by cross-party committees of the Scottish Parliament scrutinising the salmon farming industry in 2018. Major concerns over water pollution from fish and chemical waste, disease and mortality rates, impacts on other marine life, and fears that the economic benefits of the sector had been exaggerated, led both committees to recommend reform of the sector’s regulations and operations before the Scottish Government allowed its expansion ambitions to go ahead.

The salmon farming industry wants to expand to 300-400,000 tonnes a year by 2030, a near doubling of its current size. The government has been supportive, arguing that the sector provides around 12,000 year-round, highly-skilled and well-paid jobs, often in areas where there are few employment opportunities. Around 2,000 people are directly employed in salmon farming, with the rest employed in supply chain jobs such as processing and equipment supply.

Two years on from the MSPs’ recommendations, and both the Scottish Government and industry claim that the sector is reducing its environmental impacts, with new regulations for fish farms bought in. “We advocate sustainable growth of the sector with due regard for the environment, the £880 million that the sector and its wider supply chain contribute to the economy and the £1.4 billion that is spent annually on supplies and capital investments, mostly in Scotland,” Fergus Ewing, Cabinet Secretary for Rural Economy, told the Scottish Parliament’s Rural Economy and Connectivity (REC) Committee at a hearing in December, which was called to assess the sector’s progress against the recommendations made in 2018.

Flawed economics

But not everyone is convinced by these claims. Campaigners are concerned that the economic impacts of the sector is being exaggerated, and does not take into account environmental damage that is harming other industries. Furthermore, they do not believe that recent changes brought in by regulators will lessen this.

An economic assessment published in April 2020 found flaws in the economic benefits of salmon farming cited by government and industry. The analysis, commissioned by two charities, concluded that the salmon farming industry’s estimation of Gross Value Added has been exaggerated by 124%, while employment had been overestimated by up to 251%.

It also questioned the way the salmon farming industry’s economic contribution is reported. Both industry and government have referred to a turnover of £2 billion for aquaculture companies and their trading partners, a figure which originated in a 2017 economic analysis. But the economists questioned the methodology used to calculate this, and said that turnover figures should not be used to influence public policy.

In any case, 99% of Scotland’s farmed fish is produced by just six companies, which are owned by companies based in Norway, Canada and the US, so a proportion of their profit is likely to leave Scotland, the economists surmised. Only wages, and revenues to the UK from tax, should be considered an economic benefit to Scotland, otherwise damage to its environment will largely benefit those in other countries, they said.

It concluded that the economic evidence base for expansion was “partial, incomplete, unreliable and even irrelevant”. Salmon and Trout Conservation Scotland and the Sustainable Inshore Fisheries Trust, which commissioned the study, say the government should undertake a comprehensive Cost Benefit Analysis before allowing more salmon farms to open.

Seawilding oyster bed regeneration project can help create jobs and prosperity and also regenerate ocean ecosystems

Other industries ignored

Crucially, such an analysis would take into account the negative impact of salmon farming on other industries such as inshore fishing, recreational sea angling or tourism, which has not been factored into the figures used by government and industry. Report co-author Dr Geoffrey Riddington said:

The industry’s damage to Scotland’s inshore waters must result in many other stakeholder groups being worse off. At no time has the Scottish Government even identified these groups, let alone calculated the extent of their costs.

The analysis was peer reviewed by Bridge Economics, which supported the conclusions, adding that any assessment of expansion needed to take into account the impacts on other parts of the economy, so that “a clear and dispassionate assessment of the net impact” can be calculated. This approach would also be consistent with the Green Book, which sets out the methodology the government should use when assessing economic impacts.

However, the government still does not seem to be planning any assessment of the net impact of the industry, as called for by campaigners and the Scottish Parliamentary committees. “It is not standard practice to assess an entire sector in the framework of a cost benefit analysis,” Ewing told MSPs on the REC Committee.

Salmon farmed in Scotland are plagued with sealice - photo credit Corin Smith

Negative impacts

The impacts that salmon farming has on other industries come from multiple factors. One major concern is the use of chemicals to control sea lice. Adult sea lice occur naturally in the sea, living on the skin of fish. These pests damage their hosts’ skin through feeding, which can lead to viral and bacterial infections. Infestation can cause stress and immune suppression, with greater susceptibility to secondary infection and disease.

Fish farms use various methods to control lice. The most controversial of these is a chemical called Emamectin Benzoate (sold under the name “SLICE”), which interrupts the moulting cycles of sea lice, a type of crustacean. But those working in the shellfish industry - known as creelers after the type of basket they use - fear that it also harms commercial species of crustacean such as prawns, crabs and lobsters, which live in sea lochs often in areas around salmon farms.

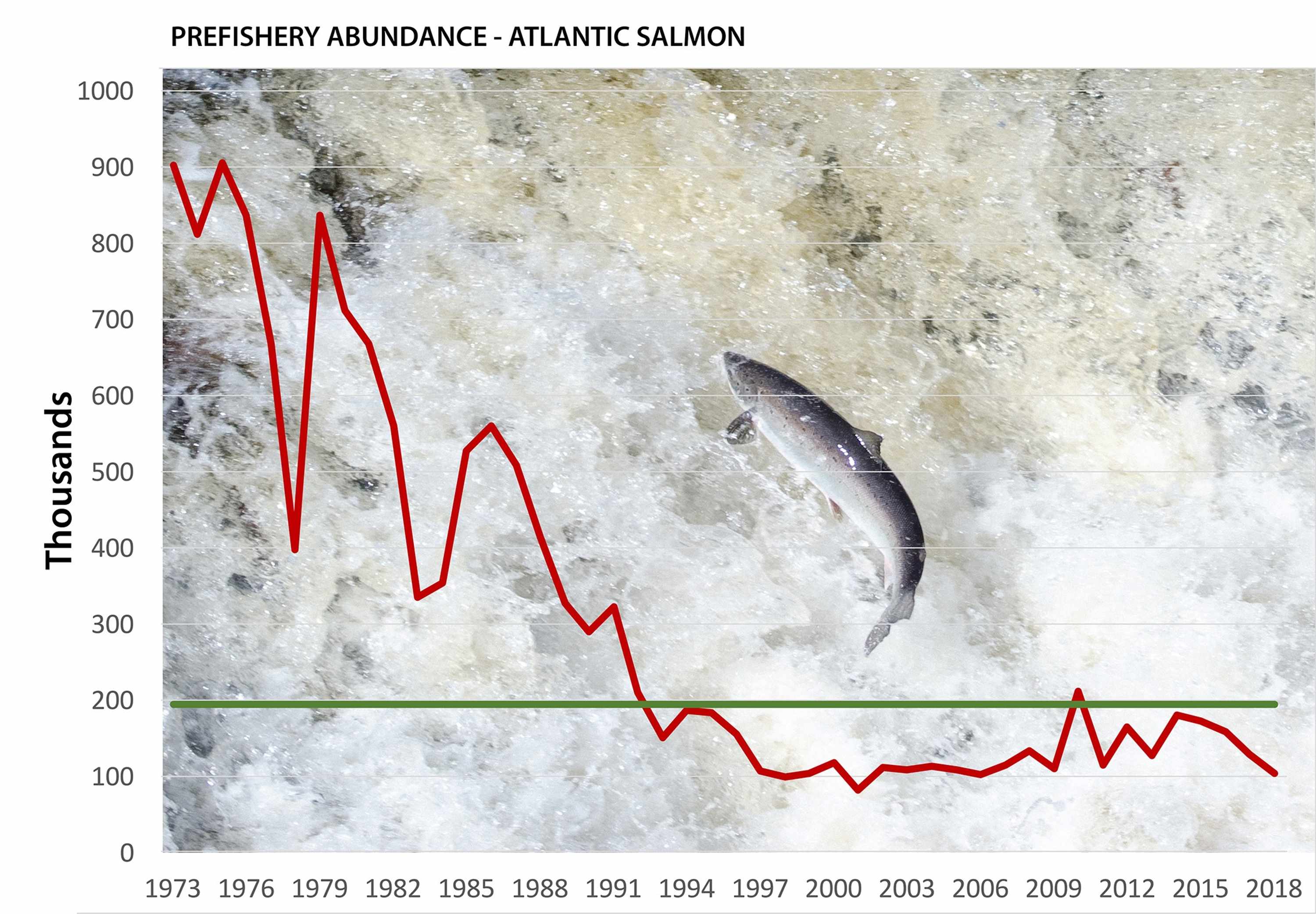

Campaigners also fear that sea lice infestations can harm wild fish swimming past fish farms, including sea trout, and juvenile wild salmon (known as smolts). Evidence of this link is “considerable”, according to a 2018 scientific paper, which points to several other studies showing that the effects can be “severe”, killing fish, and resulting in reducing opportunities for fisheries.

Andrew Graham-Stewart, director, Salmon and Trout Conservation Scotland said -

We want effective regulation, particularly on wild fish impacts. This must include an upper limit on sea lice numbers on farms, with independent monitoring and verification of those numbers. And when numbers exceed the ceiling, there must be proper sanctions which should include reduction in biomass on the farm, or early harvesting,

The Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA), which is responsible for licensing fish farms and enforcing against damage to the water and seabed, has acknowledged that the existing rules on the use of the chemical are not adequate to protect marine life, and has asked the UK Technical Advisory Group - a partnership of environment and conservation agencies that advises on standards to protect the water environment - to make recommendations on new standards to the Scottish Government.

In the meantime, SEPA says it has produced much tighter interim standards for the use of the chemical at new farms and major expansions of existing sites. It claims these standards are so low that SLICE can effectively only be discharged in very limited quantities.

But Sally Ann Campbell of trade body the Scottish Creel Fishermen’s Association (SCFF) said that there was increasing concern about the cumulative impact over time of the chemical, which accumulates in sediments underneath farms, or is carried into the wider ecosystem by tides. Research by SEPA in Shetland found that it remained in the environment far longer than expected.

Legislation bringing in an improved reporting system was introduced at the end of last year, according to evidence given to the parliamentary committee. Every fish farm is now mandated to send weekly reports of sea lice numbers to Marine Scotland. However, Andrew Graham-Stewart, director of Salmon and Trout Conservation Scotland, said that the new arrangements fell far short of what is required.

“Fish farms are marking their own homework – they declare what parasite numbers are, what their disease impacts are, what their mortality rates are, so there’s every incentive for them to downplay matters. We need a proper programme of independent monitoring and independent verification on fish farms,” he said.

Charles Allan, head of fish health inspectorate at Marine Scotland, told the REC Committee hearing that in the past year, it had served two enforcement notices to fish farms, both of which related to sea lice. “Limited action has been taken but, as a regulator, I am limited by the sanctions that are required in the legislation,” he said. In-person inspections had been paused due to Covid-19, but the regulator had since resumed these for high-risk sites, he said.

Enforcement notices comprise a letter stating that lice numbers must be brought down within a month – “very far from robust enforcement”, according to Graham-Stewart.

A common seal and her pup - photo credit - Sealife Adventures

Tourism impact

The wildlife tourism sector is also concerned about the impact of salmon farms, in particular, the impact on porpoises, whales and dolphins, as an unintended consequence of controlling attacks by seals. Trade body the Scottish Salmon Producers Organisation (SSPO), says that half a million farmed salmon in Scotland died as a result of seal attacks in the year to May 2020.

Fish farms have been allowed to shoot seals – 31 were shot in the first three months of last year - but this was banned at the end of January 2021. Fish farms also use Acoustic Deterrent Devices (ADDs), which make a loud noise underwater, to scare seals away.

However, campaigners say that the noise from ADDs injures porpoises, whales and dolphins, which are protected from disturbance by law. David Ainsley a marine biologist who runs wildlife-spotting boat trips through his company Sealife Adventures in the Forth of Lorn, a designated Special Area of Conservation near Oban on the west coast of Scotland, said that a study by a researcher at Edinburgh Napier University found a 286% increase in cetaceans where there are no ADDs. However, a nearby area where two farms use multiple ADDs, bottlenose dolphins sightings are now rare, he says.

Though it denies that ADDs injure marine wildlife, the SSPO says that it is working with the University of St Andrews to research the issue, and is also looking into alternatives, such as double nets.

Double nets – where a normal fish net hangs inside a steel outer net – are widely used in other parts of the world such as Canada and Australia, and have proven very effective at protecting farmed fish from seal attack, according to Ainsley. Some salmon farms in Scotland are switching over to this method, he added.

However, the transition in Scotland has been slow because Marine Scotland has “pandered to fish farms doing things the cheapest way rather than the best way”, he said. Use of ADDs increased from 133 in 2018, to 142 in 2020, according to official data. Just 32 farms used double mesh netting panels in 2018. Ainsley fears that more farms will want to use ADDs due to the ban on shooting seals.

Marine Scotland is now requiring fish farms to apply for an annual European Protected Species (EPS) licence for the use of ADDs, for which they will have to meet three tests, including that there is no satisfactory alternative to their use. “Double nets are used instead of single ‘traditional’ nets in Shetland, British Columbia and elsewhere, so no reasonable authority could accept that ADDs pass this test, Ainsley said.

In total, deaths of farmed salmon, lice treatment, impacts on other fish and pollution could have cost industry and society as much as £3.3 billion between 2013 and 2019 – costs which are rarely quantified, a recent study by Just Economics.

Bottle nose dolphin seen off the coast of Oban - photo credit - Sealife Adventures

Expanded industry, expanded risk

Environmental campaigners want to see fish farming cleaned up before any further expansion is allowed. Since the two Parliamentary inquiries reported in 2018, an extra 33,000 tonnes of new farmed fish production has been licensed by regulators, according to John Aitchison, from the Coastal Communities Network.

There is a case for fish farms due to the the jobs, he says -

But should they do harm when they have alternative methods? They could use closed nets, which would protect them from sea lice so they wouldn’t need chemicals, and they could capture the excrement from the fish and dispose of it like any other farm.

Overall, progress since 2018 had been “excruciatingly slow”, Aitchison says. Though pollution regulations had been tightened a little, all fish farm pesticides were still being dumped in the sea, with no assessment of the impact on commercial fishing catches, nor whether Scotland’s coastal waters could assimilate twice as much pollution, as the industry doubles in size, he says.

“Clearly ministers are in no hurry to bring forward new regulations to address these problems, all of which affect other users of the sea, until this uniquely-favoured industry has achieved its expansion plans,” he says.

Campbell added: “Until it is recognised that the employment figures and monetary value to the Scottish economy is grossly overblown, and that the damage to ecosystems and spawning grounds is recognised, nothing will change. Marine Scotland and SEPA as agents of the government are not facing up to the reality.”

Wild salmon numbers keep declining