Big food and energy corporations are burning our planet for profit but inspiring leaders show another way is possible

By Matt Mellen Would you still drive a diesel car if you knew that rainforest had been cut down to fill your tank? When rainforest is cleared, creatures lose the only habitat in which they can survive. We are living through Earth’s Sixth Mass Extinction event; ecological systems are breaking down and species dying off at an alarming rate. Does the responsibility lie with us, the consumer, to make enlightened choices to prevent the damage? Or does the responsibility lie with the multinational corporations that tear down the forest and the governments that enable them? At what point do we challenge the neoliberal economic system itself? How can it make sense to use rainforest as fuel when we need a functioning planet to survive and we already have the technological prowess to power cars directly from sunlight? Adopted in 2009, the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) promotes the use of biofuels in Europe. As a result, the amount of palm oil used in biodiesel has increased significantly. Most consumers have no idea that palm oil is in their fuel but cars and trucks now burn almost half the palm oil used in Europe. Experts are widely critical of this misguided environmental policy, which drives bad outcomes, for example, burning biodiesel made from palm oil causes, on average, three times the climate damage of fossil diesel.  Palm oil plantations destroy forest and animals cannot survive

Gero Leson is Vice President of Special Operations at Dr. Bronner’s, a top-selling brand of natural soaps. He has helped establish organic and fair-trade projects in Sri Lanka, Ghana, India and Samoa in order to ensure his business has sufficient supply of organic and fair trade coconut, palm and mint oil, the primary raw material for their products.

SUPPORTED BY HEROES LIKE YOU

Support independent eco journalism that drives real change.Dr. Bronner’s contributed to a campaign to ban the addition of palm oil into diesel fuel in the EU. Leson’s key concern is for biodiversity. When the price of crude oil goes up, demand increases for the cheaper palm oil that is added to diesel fuel and heating oil. This encourages the giant agribusinesses to expand further into the rainforests of Indonesia, Malaysia and Borneo with catastrophic effects on the wildlife there, including the endangered and beloved orangutan.

Leson advocates businesses taking more responsibility for sourcing of their raw materials to ensure they cause no harm and, ideally, shifting to having a beneficial impact in the areas where they operate: “The problem with the mass production of palm oil is that corporations are doing it on a vast scale using industrial methods - monoculture production with high levels of petrochemical inputs.

Our model of farming supports small-scale family farmers who, when working organically, can improve the productivity of their smallholdings without the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides”. These smaller farm units, essentially small businesses, than hire people who work skillfully within diverse plots that allow wildlife to co-exist with farm production. If industrial scale plantations transitioned to these models of regenerative agroforestry we could meet global food demands without further forest destruction. 14 million hectares of Indonesia are oil palm plantations, which equates to almost half the area of Germany.

Studies have identified a further 1.37 billion hectares of suitable land for oil palm cultivation, concentrated in twelve tropical countries, but this would be a further devastating blow to wildlife, as well as our atmosphere, and it’s not certain that the forest would ever recover. Industrial farming methods damage soil and interrupt water cycles. When all the nutrients have been sucked up by the plantations, sometimes only desert remains. Regenerative Agriculture in Benin by Fabrice Monteiro

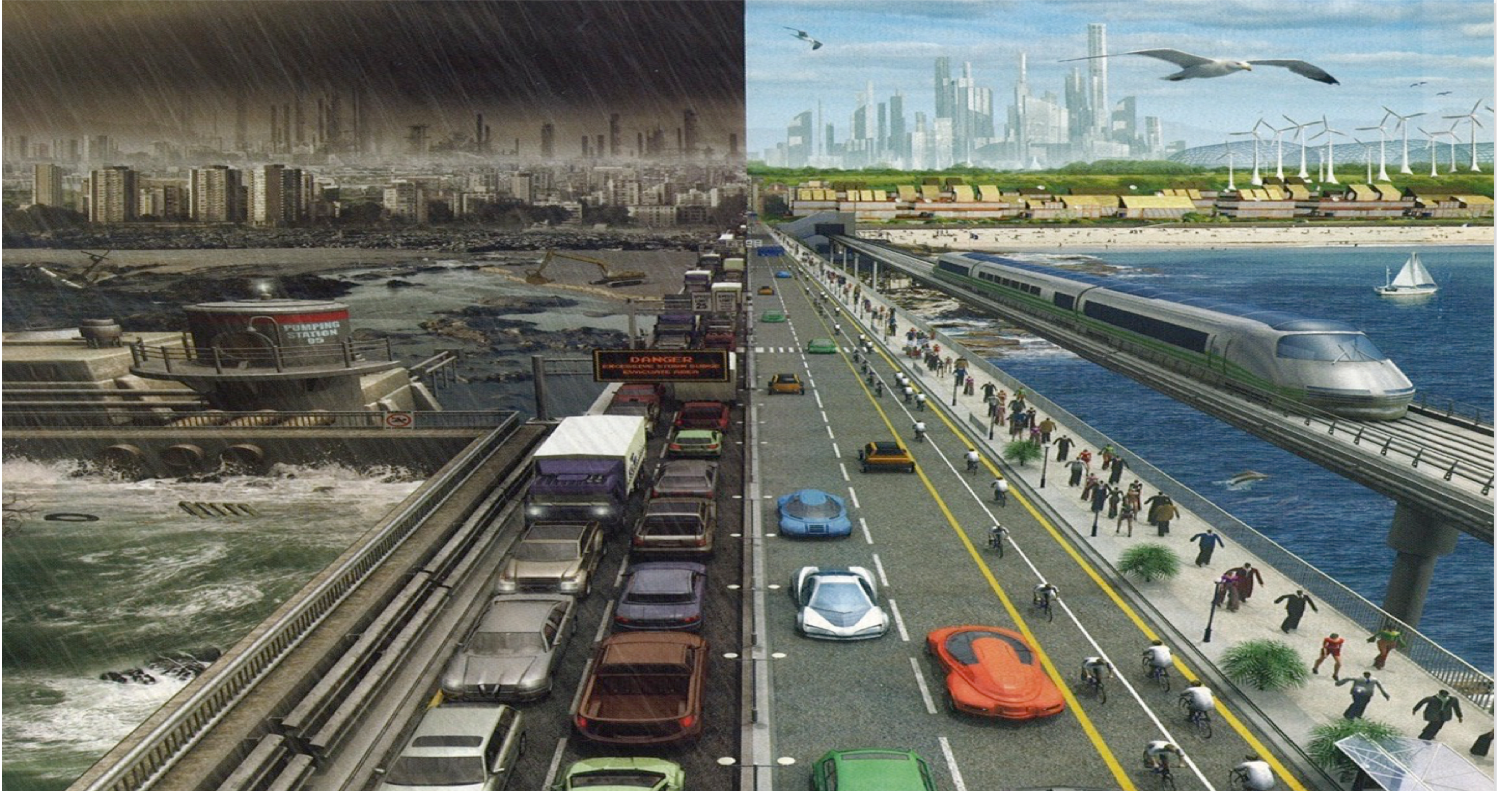

However, two key pathways to a sustainable future have been identified. The first is transforming agriculture from being a destructive resource drain into a regenerative force, which builds soil, absorbs carbon from the air and creates abundant, healthy food near to where it’s consumed. The second depends on executing The Great Energy Transition - rapidly phasing out fossil fuels and creating a joined-up renewable electrical infrastructure that connects concentrated solar thermal arrays in remote deserts into charging electric cars plugged into efficient homes in smart cities. Many of the biggest economic entities on earth are the giant petrochemical companies that fuelled the age of heavy industry. Exxon Mobil alone is economically larger than Ireland. These giants have become adept at broadcasting their agenda and it’s widely believed that fossil fuels are essential to feed the world. However, fossil fuel-driven farm production and petro-chemicals have degraded soil, drained lakes and created giant dead zones in oceans, so this propaganda is revealed as fake news. Industrial food production isn’t the solution it is the problem. A sustainable future society depends on the citizens of the world untangling the complex corporate Big Food / Big Energy nexus that is behind most planetary ecocide.

The British social entrepreneur and writer Jeremy Leggett has written four books on the climate / energy nexus, most recently, _The Winning of The Carbon War_, covering the dawn of the global energy transition. He says: "At a time when the price of renewable energy is falling and the technology is improving it is madness to be converting rainforest into new palm oil plantations to create fuel for cars. For a range of reasons, we need to be shifting away from the internal combustion engine and moving to electric transportation powered by renewables. Creating new markets for plant oils only benefits large agriculture corporations and creates significant problems, from climate change and pollution through to biodiversity loss." Like many renewable energy entrepreneurs, Leggett sees an important shift ahead from large, centralised energy giants to smaller, distributed energy companies. Interestingly, an analogous shift is being lobbied for in the food system too. The Gaia Foundation - headquartered in London but working across the global south - advocates for small farmers and the protection of cultural and biological diversity. They have created a stunning photographic exhibition (currently on tour) depicting the work of small-scale farmers called We Feed The World. This important exhibition illuminates the skills required to grow food without machines and fossil fuels. Speaking at their event in London, Theo Sowa, Chief Executive of the African Women’s Development Fund said: "When it comes to food and farming around the world, we need to change the narrative about small-holder farmers. Changing the narrative about how we feed our world. Changing the narrative about what food can mean to us, does mean to us, how we can grow it and how we can have a different relationship to it. If we in our world can stop thinking that food is about a massive industrial system then we can encourage not only the farmers that are working now, but also the next generation of farmers.”  Charles Dowding's legendary garden in Somerset, England

Small-scale farming is also being encouraged in developed countries. Charles Dowding, a UK-based food grower, author and teacher thinks that many more people could grow food – and improve its quality and sustainability. He has converted the garden of his home into a stunningly productive plot that is visited by people from all around the world who are keen to learn how it’s done. He is adamant that increasing local food supply is both feasible and desirable: “It looks to me that governments are too aligned with corporate interests for anything to change at the macro scale. So the only solution for making things better is what we can do ourselves, and growing food is one possibility. I see my work as encouraging and helping anyone with access to land or just a balcony to grow healthy food, connect with nature through plants and be less dependent on a system that looks increasingly fragile, both economically and ecologically.” From school yards, roofs and car parks through to back gardens - there are many spaces near people’s homes that can be converted for food production. Not only does this avoid the destructive corporations, it delivers higher quality food without the food miles and also creates meaningful work for many people. Detroit is an oft-cited example of where independent food growing emerged unexpectedly in a post-industrial landscape with multiple benefits for local communities.  Both the energy transition and tackling corporate control of global food supply requires the rapid disruption of outdated thinking. Corporations wield disproportionate power in the “free” market. If it suits the business model of giant agricultural and petrochemical companies to add plant-based oils into the fuel supply they will do this regardless of the damage it causes. In a capitalist system that serves only the shareholder this must surely sound the alarm that we cannot stand by and hope that existing industrial institutions will solve the many challenges currently facing society. If scientists’ warnings are heeded, humanity’s collective mission will shift from industrial development to preserving the world’s ecosystems. This will require new ideas, processes and businesses. A widespread, citizen-led revolution in how food is grown, prepared and brought to the table could tackle multiple problems from unemployment and obesity through to climate change and biodiversity loss. At a time of converging crises, an earthy solution is right under our feet. Making sustainable food production central to more people’s lives could fundamentally redirect the economy to a new, healthier trajectory. A future ‘ecological age’ beckons, where humans thrive within an abundant biosphere. How we feed ourselves is a fundamental upon which this future civilisation depends. When people are more closely involved with the local food systems that sustain them, anomalies like food crops from rainforests being used for fuel could be consigned to the past. Time is tight but the prospects are good. A sustainable food revolution will benefit humans and the planet’s ecological systems alike.